26.03.2015

Museum Week 2015

This week was international Museum Week, an opportunity for Museums from all over the world to celebrate their culture on Twitter. For each of the 7 days a new theme is explored using a different hash tag.

- Monday – #secretsMW – Museums and cultural establishments from all over the globe welcome you to their everyday world and introduce you to work behind the scenes… and perhaps a few well-kept secrets!

- Tuesday – #souveneirsMW – Share your souvenirs and memories of visits: photos, mugs, books, postcards, encounters and special moments!

- Wednesday – #architectureMW – Explore the history, architectural heritage, gardens and surroundings of museums.

- Thursday – #inspirationMW – Now it’s your turn to create and share for posterity! Art, science, history and ethnography are all around us. To your smartphones!

- Friday – #familyMW – With the weekend almost here, prepare family visits or upcoming school trips with advice and tips from the museums themselves.

- Saturday – #favMW – Now the weekend has begun, share your special favourites (works, conferences, locations, etc.) in 140-character messages, videos, photos or Vines.

- Sunday – #poseMW – This last day of #MuseumWeek 2015 is all about creativity! Poses, memes or selfies… it’s up to you!

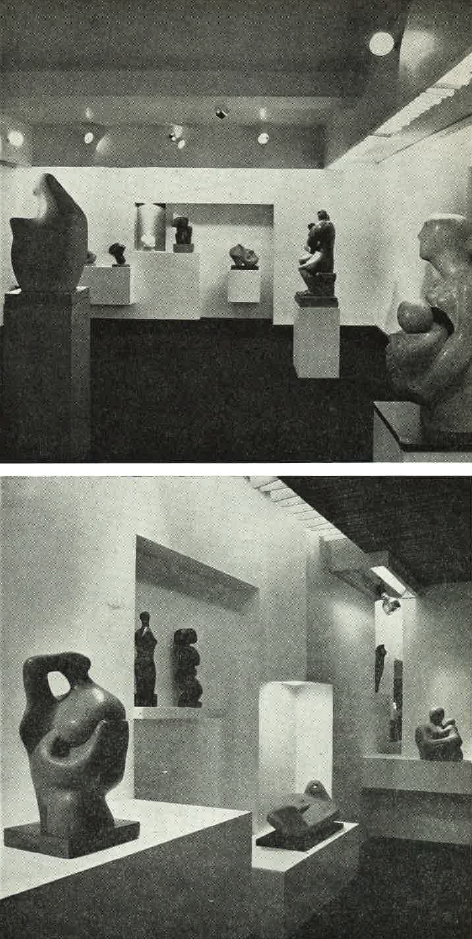

The Chartered Society of Designers has a remarkable history and a vast amount of archive material that we have accumulated since the Society began in 1930. As our contribution to #MuseumWeek this year we have decided to share with you an extract from the Society of Industrial Artists journal, June 1964, featuring Museum and Display Design including an exhibition of the early work of Henry Moore at the Marlbrough Gallery, designed by Richard Burton, as well as articles by Loraine Conran the director of the City of Manchester Art Galleries.

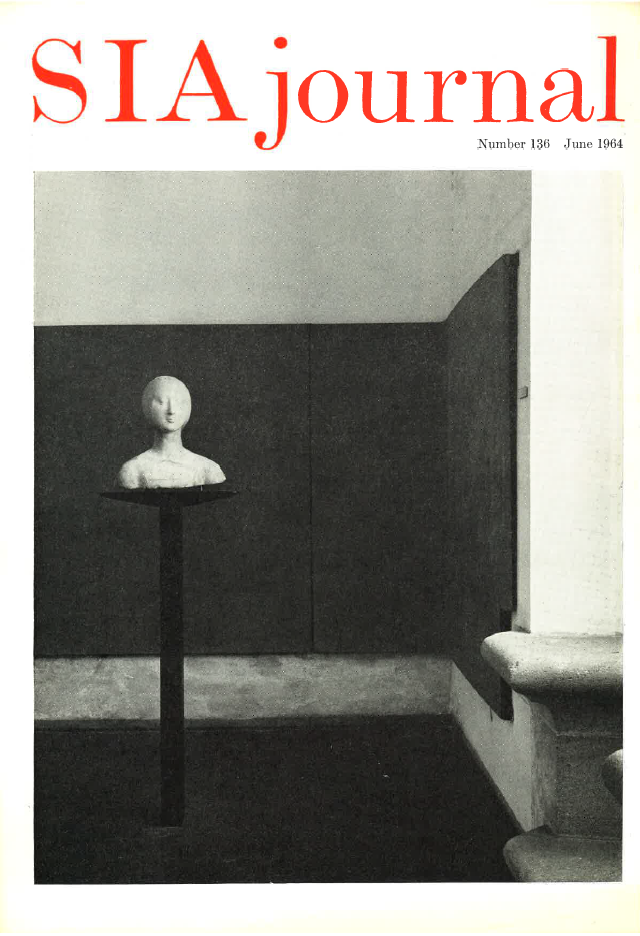

SIA Journal no.136 (June 1964) cover: The bust of Eleonora d’Aragona by Francesco Laurana in the Palazzo Abbatellis (architect Carlo Scarpa), Palermo.

A Big Question Mark hangs over the museums and art galleries of this country. Some are the best in the world. But many are in a bad way. Some, deprived of money, adequate staff and even visitors face bankruptcy and closure. Others need vigorous pruning and re-organisation. The rest, bursting at the seams with some of their best possessions in storage, urgently need new, modern buildings.

There are 876 museums in the country. Thirty-five years ago there were half this number and only fifty existed in 1850. The oldest museum, founded in 1613, is the Ashmolean at Oxford, closely followed by the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society Museum. The great period of museum expansion was in the second half of the nineteenth century when local municipalities opened them as a kind of cultural Sunday School for the edification of the labouring classes. By the 1930s a new museum was opening every three weeks.

Today half are run by local authorities; 90 are military museums; about 55 belong to Universities; a few, such as the Tower of London, are controlled by the Ministry of Works, others-such as the glass museum being designed by James Gardner at St Helens-by professional or commercial groups; the rest are private. Some like the City Art Gallery, Manchester, have an annual attendance of about 263,000 people, while others such as Nottingham University Museum have as few as 300 visitors a year.

Collections of fine art and antiques at Oxford, Cambridge, Liverpool and Glasgow are incomparable; there are distinguished post-war collections like the prints and drawings built up by Miss Margaret Greenshields at the Cecil Higgins Museum at Bedford; and up and coming museums like Manchester, under its new Director, Loraine Conran, are starting new progressive policies.

On the other hand, contemporary art is almost non-existent in the provinces, the standard of scientific and industrial museums is very poor, there is no national folk museum, the toy museum has no permanent home, and in spite of the richness of ethnographical material in this country it is mostly hidden away in gloomy rooms in cases reminiscent of school lost property cupboards.

Too many museums are in hideous, ill-lit Victorian buildings, the soulless mortuaries of dusty overcrowded and inadequately labelled objects; and among the squalor of the second rate some galleries have priceless pictures or objets d’art which they have neither the staff nor the facilities to look after properly. Some museums are doss houses for miscellaneous bits and pieces nobody wants to give away.

There has been some museum rebuilding since the war, and there are plans for at least 150 new buildings or extensions. But many of the most important shcemes still have no starting date. There is nothing in this country like the superb new museums in Europe, Japan and the USA.

Museum Display and Design

By Loraine Conran, Director of the City of Manchester Art Galleries

The contents of many of our museums are among the richest and most beautiful in the world. But their display, compared with many collections in Europe and the United States, are too often inadequate for both the specialist and the layman. But there are now signs that we intend to catch up. Yet as the following article explains, there are many pitfalls. The chief of which may be to try and turn museums wholesale into amusement centres or into little mopre than branches of the local education authorities. Basically, however, there are two broad types of museums: the conservatories of valuable works of art and the information centres of a newly leisured and curious, but basically narrowly educated, society. Both are equally important. But it would be a tragedy if the desire for better, more modern museum design damaged the value of the former or allowed exhibitions themselves to become more significant than the collections.

Museums first came into being as a public expression of the private collector’s ‘cabinet of curiosities’. The accent was on collection and conservation, display was not a conscious aim of the early collectors or the early museums.

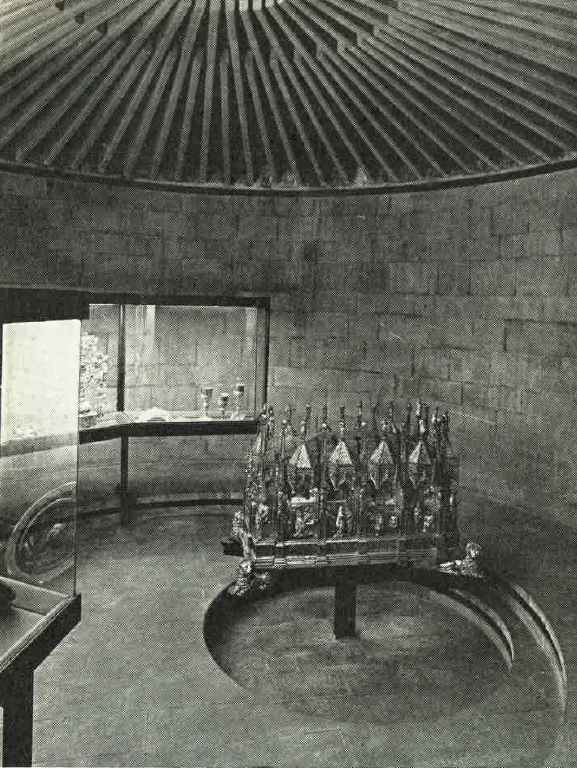

Even today the great majority of museum curators would put their duty to their collections well ahead of their duty to the public or to education or to anything else. The purpose of a museum was summed up by a Director of the British Museum as ‘The preservation of truth’. A similar philosophy was expressed by the Director of the Capodimonte museum in Naples, one of the most successfully displayed museums in Europe. He said that the guiding principle of the museum’s remodelling had been in respect to the object.

This attitude of the museum professional is found tiresome by many but if museums were ever to become primarily a source of entertainment or as serving some political or other extraneous purpose then their whole value to the community would be weakened. Fragile objects would be bumping round the globe to every trade fair and the stimulation of contact with real objects which is so valuable to adults as well as children might take second place to the striking photograph or the plastic cast, in both of which the truth is manipulable.

Most forms of display used commercially employ a form of exaggeration or at least concentrate on favourable aspects. Commercial displays have commercial objectives. They must sell something, create prestige or persuade someone to do something he has never done before like buying a ready-made suit or drinking tinned beer. If a certain measure of exaggeration is introduced, if eating chocolate or smoking can be connected with sexual success or owning large sports cars it is no disadvantage to the advertiser.

This is an attitude that museum display must treat with caution, to present a suspect Cézanne as if it were unquestioned, carefully lit and hung to disguise its imperfections and with a label quoting favourable opinions only, would not be acceptable. To present uncritically a doubtful ownership in order to heighten romantic interest-‘The poet’s writing table’ or ‘His Lordship’s wooden leg’ would also be misleading if the connection was not founded on fact.

Movable display cases which can be reassembled in different positions in the Galleria di Palazzo Ross, Genoa.

I do not want to give the impression that design has no place in a museum, but to show that in spite of superficial resemblance the aims and objects of a museum are quite different to those of a retail shop or a trade fair. I may also have explained why a proper appreciation of the necessity for good design and of the benefits it can bring has been so slow in gaining acceptance from the museum profession.

Design is no part of a scholar’s equipment. The qualities and the time it takes may well be inimical to scholarship. The grudging financial support given to any cultural activity in this country has prevented the obvious solution which is that there should be specialists in museum design just as there are specialists in archaeology, art, zoology and other museum subjects. Other countries accepted this long ago which is why most of the examples of good design in museums are to be found outside the British Isles.

The situation in England is changing. The British Museum has led the way and some of the large provincial museums such as Liverpool have also appointed keepers of design to work alongside the keepers of existing academic departments. Some of the smaller museums are served by area design or exhibitions officers. The Museums Association has had good display in the forefront of its aims for more than half a century. Its conferences and its journal have pressed the claims of good design whenever possible.

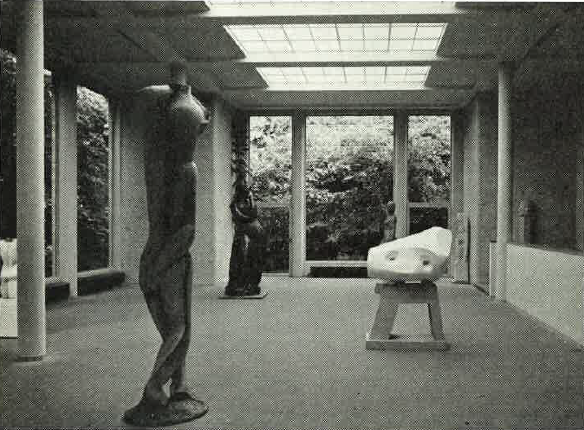

Not all applications of design to museums have been successful. There is a danger that an architect of talent may impose such a strong personal style that the exhibits become merely one element of that style. To remove the frame from an old master painting and stand it on a spike in the middle of the floor interferes with the operation of perspective which requires a rectangle and a plane surface against which to react: to place a piece of classical sculpture on a turntable makes it part of a mechanical device. In each case the object is made more striking but is diminished aesthetically. This would not be the case with a mobile which is conceived with movement, nor in the case of many contemporary paintings which either do not use perspective or do not use it in an illusionist way so that these methods of display could be used legitimately for contemporary work.

One of the most brilliantly designed museums in the world; the sculpture gallery in the Kroller-Müller museum at Otterloo in Holland.

Good design, without any loss of integrity, can make facts more easily assimilable to the unspecialised ordinary museum visitor, it can make the true qualities of a work of art understandable to those with no knowledge of art history or modern art and it can help to attract vastly more of those people who may find Bingo and the dogs an unsatisfactory way of filling their growing leisure. This is why design is so crucial.

Good design can do other less obvious things in the museum. It can renew the obsolete Victorian buildings with which most of us are saddles or it can provide new buildings which are accessible centres of culture rather than hushed temples of the arts for an élite. It can produce new methods of storage that make reserve collections readily available to the scholar and enquirer. In general it can increase the use and enjoyment of the great resources in our public collections by all sections of the community.

The original magazine article can be viewed here: SIA Journal, no.136 June 1964